16-08-04

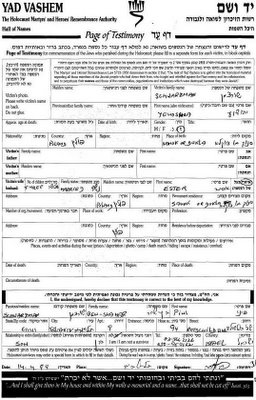

Research in Yad-Vashem found that Moshe and Yitzhak Schwartzman are stepsons to Friede Briendel (Boimel) and Zvi Dov (Hersh Ber)

בדיקה ביד ושם גילתה כי משה ויצחק שורצמן התייתמו מאמם שנפטרה צעירה, אביהם צבי דוב נשא לאישה את פרידה ברינדל לבית בוימל והם ילדו 7 ילדים נוספים שאף הם כנראה ניספו בשואה

בתמונה צבי דוב בצילום שצולם כנראה

בתחילת המאה ה-20 1910-1920 התמונה נמצאה

בספר הזכרון של קהילת לינסק (לסקו) שאחד ממחבריו היה בנו יצחק שורצמן שעלה לישראל ב 1933 וניצל

בתמונה למטה שאף היא נמצאה באותו ספר זיכרון מצולמים כנראה 7 ילדי צבי ופרידה שעל פי מסמכי יד ושם נספו כולם בשואה. יצחק ומשה (הילדים החורגים) מצולמים כאן.

שורצמן נפתלי שנולד בסנוק ב 1929 RelatioNet SC NA 29 SA PO

שורצמן אסתר שנולדה בסנוק ב 1917 RelatioNet SC ES 17 SA PO

שורצמן לייב שנולד בסנוק ב 1922 RelatioNet SC LI 22 SA PO

שורצמן שושע ? שנולד (ה) בסנוק ב 1928 RelatioNet SC SH 28 SA PO

שורצמן דבורה שנולדה בסנוק ב 1926 RelatioNet SC DV 26 SA PO

שורצמן רחל שנולדה בסנוק ב 1919 RelatioNet SC RA 19 SA PO

שורצמן בן-ציון שנולד בסנוק ב 1912 RelatioNet SC BE 212 SA PO

דפי העד ביד ושם של בני המשפחה מולאו על ידי יצחק שורצמן בשנות ה 50 בת"א

סיפורו המרגש של ספר תורה שעבר את תקופת השואה באורווה פולנית תחת צלב קרס ויוכנס בשבוע הבא לבית כנסת בעיר מודיעין.

עמיעד טאוב 08/05/2007

הרב אברהם גראניק

כשמונה הרב אברהם גראניק לתפקיד רב העיירה לינסק (לסקו, Lesku) שבפולין לאחר שאביו הרב אריה גראניק רב העיירה הקודם הלך לעולמו לאחר 57 שנות כהונה לפני כשמונים שנים החליטו חברי הקהילה היהודית בלינסק לכתוב ספר תורה חדש לזכר רבני העיר בני משפחת גראניק. למען כתיבת הספר הובא במיוחד סופר בעל שם מהעיר קראקוב שהקפיד לטבול במקווה לאחר כל חצי פרשה אותה כתב.  בית הקברות ומעקה מרפסת באחד מבתי העיירה עשוי ממעקה הבימה של בית הכנסת הגדול

מי הוא יהושע שורצמן ואיך הוא קשור למשה שורצמן 0545728608 035662126 אבי שניבאום 03-5731845

שיחת טלפון ביום 26/12/05 עם פיני [פנחס] בן שחר [שורצמן] פנחס בן שחר, בתי תל אביב יפו מספרים, תולדותיה של העיר העברית הראשונה, משרד הביטחון ההוצאה לאור, תש"ן - 1990. מעוררת סיכוי שמדובר בבני אותה משפחה. פיני נפגש בשנות השבעים עם משה פנחס שורצמן במקום עבודתו ברחוב טרומפלדור בת"א שסיפר לו כי הוא קרוב משפחה, הוא נפגש עם חיה צוקר בשנות השבעים בקפה עטרה בת"א פגישה בה היא סיפרה לו על אביו, הגב' צוקר היא קרובת משפחה ידועה של משה פנחס שורצמן [אמה רישה אויבלום היתה בת דודה ראשונה של משה] .

פיני גם סיפר כי ב-34-35 בת"א בהיותו כבן 4 פגש את יצחק שורצמן שעבד במחלקת המים בעיריית ת"א יצחק סיפר לו כי הוא קרוב משפחתו מצד אביו שנשאר בפולין.

אמו אסתר ו 2 אחיו, אריה הבכור ומשה עלו לישראל לפני השואה בשנות השלושים האב יהושע נשאר בסנוק וכנראה נספה.

3,000 in Rebel Band Terrorize Galicia

Ukrainian Nationalists, German Deserters Led by SS Colonel Burn 3 Villages in a Night

By Wireless to The New York Times

(The article appeared The New York Times on April 18, 1946)

Sanok, Poland, April 17 – A strong, well-organized and elusive band of Ukrainian nationalists and German deserters estimated at more than 8,000 under the leadership of a German colonel, in a fortnight have succeeded in transforming this sector of the Carpathian foothills of old Galicia into a virtual partisan stronghold.

With the burning of three large villages on a single night two weeks ago, they now have made 10,000 of this areas total pre-war population of 135,000 homeless and are resisting with complete success all efforts to quell what is tantamount to open insurrection. By burning an average of two bridges a day for the last three months, they have completely disrupted communications in this thickly populated but primitive backwoods country and have made it virtually impossible for security police and two Polish divisions to rout them out.

By stealing cattle and demanding tributes of a million zlotys [about $10,00] they appear capable of holding out indefinitely in their wooded hide-outs.

Objected to Repatriation

The origin of the insurrection is more complex than obscure. It began when under the repatriation agreements, the Ukrainians were to be shipped back to the Soviet Union and their farms given to Polish repatriates from what is now the Russian zone of former eastern Poland. Many refused to return and took to the hills. There as nearly as the story can be pieced together, they met and were incited by small bands of armed German deserters, including officers familiar with the tricks of partisan warfare.

Gradually the small bands joined forces with a leader said by Polish officials to be a German SS [Elite Guard] colonel, which is plausible, since the Ukrainian SS was organized by the renegade General Pethuse, whom the Germans reportedly liquidated in 1943 after he had served his purpose as the rallying point for the traditionally anti-Communist Ukrainians.

The present insurrectionist leader is known by all – by peasants and officials alike – as “The Colonel,” The band itself is known as the Banderowce, after one Colonel Banderowce, a Ukrainian who apparently became a legend in this part of the world for his fight with the Ukrainians against the Communists after the last war.

Tribute Demanded

The writer of this dispatch last week went to the heart of the bandit country to the village of Bukowsko, where on the night of April 4 the bandits burned down all but eleven of the 400 houses and made more than 3,000 persons homeless. Our escort consisted of the refugee Mayor, now in Sanok and two squads of well-armed Security Police under the command of a nervous 20-year-old second lieutenant.

Before burning the village the bandits, who were well armed with German and Russian automatics and machine guns, had demanded 1,000,000 zlotys tribute, and the village had raised 300,000. On the night of the fire the villagers received scant warning a few hours before from a peasant that the bandits were coming, but had not had time to remove their cattle. Among those in Bukowsko was Andrew Kotalik, who in 1924 returned to Poland from Jersey City, where he had worked as a boilermaker with the Lackawanna Railroad.

“From the war,” he said in English, which he had not spoken in twenty years but which he still had a Jersey accent, “we ain’t had enough. From the Joimans we ain’t had enough. Then them bandit fellas come and they boint down the houses and boint my horse and four sheepses. Excuse my English, I ain’t spoken for so long. But can you folks do something for us folk?”

Aid from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration has not yet reached the bandit country, but the Caritas organization has received and is distributing the first shipments of food, clothes, and medicines.

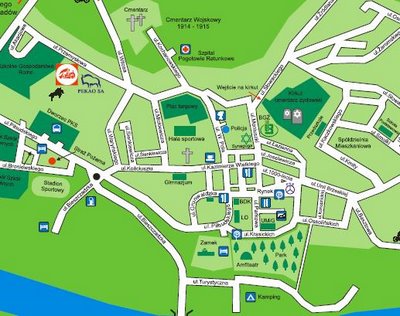

Lesko

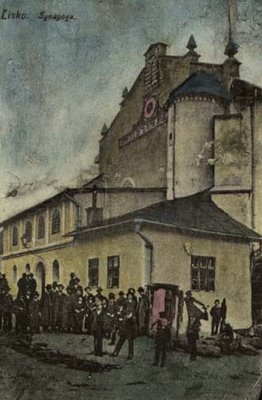

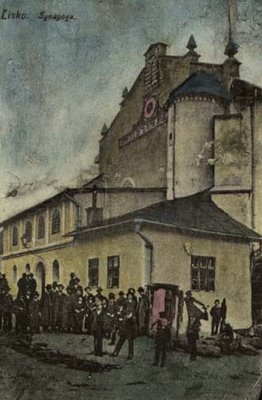

Lesko is situated about 15km from Sanok but geographically on the eastern side of the San river. It is the gateway to the Bieszczady mountain region. During the war, Lesko was occupied by the Russians until 1941. In September 1939, my father was able to leave Sanok and reach family in relatively-safe Lesko (from where he was later deported to Siberia). Lesko has a beautiful synagogue which was rebuilt in the 1960's. The synagogue tower was once used to hold Jewish prisoners. Now housing an art gallery, the lobby of the synagogue has memorial posters to the destruction of Polish Jewry and the victims of Lesko, more...

The texts presented here were originally published in the guide Where the Tailor Was a Poet..., by Adam Dylewski (Pascal).

Tourist Attractions

The late Gothic parish church of the Visitation of the Most Holy Virgin Mary (first half of the 16th century), remodelled (the neo-Gothic tower from the end of the 19th century); the Kmita family castle from the 16th century, with a dwelling tower in late Gothic and Renaissance styles; the 16th-century fortifications, now terrace gardens; the houses from the 18th and 19th centuries, including an inn. Lesko is a starting point for trips to the north-east ranges of the Bieszczady and Gory Slone. The Zalew Solinski (an artificial lake on the River Solina) with numerous recreational centres is located 16 km to the north. The first settlers arrived in Lesko sometime before 1542 and made their living from trade, butchery, goldsmithery, brewing and tailoring. Many travelled with their goods even to distant mountain villages. The kahal was formed at the end of the 16th century and assumed adominant position in the Sanok area. The end of the 18th century saw the rise of Chasidism, which triumphed in Lesko as well. Even tzaddikim appeared here, the best known being Samuel Szmelke. Deterioration in the town's economic situation in the 19th century meant that many Jews began moving to neighbouring villlages. In September 1939, Lesko found itself inside the Soviet Union. Jews were persecuted for ideological reasons, although the criterion was not race, as under Nazi occupation, but social standing. They were deported into the depths of Russia. The Germans arrived in Lesko on 24 June 1941. They established aghetto, which they then liquidated in August 1942, sending all those imprisoned there to death camps.

The Synagogue

The synagogue was built sometime between 1626 and 1654, and so the middle of the 17th century is most often cited. The building was not heated, so it functioned only in summer. In winter the main prayer hall was used for Friday night and Saturday morning services only. On all other occasions they were held in two small prayer houses adjacent to the entrance. After several hundred years of peaceful existence the synagogue was seriously damaged by the Germans. Twenty years after the war it was still in ahalf-destroyed state.

|

| The synagogue, photo: |

Erected in stone and rectangular in shape, it has an extension containing aprayer room for women. The inscription on the front wall proclaims: "What fear this place fills us with! There isnothing here but ahouse of God". The aron ha-kodesh is framed by half-columns crowned with atympanum, similar to that in the famous but no longer existing Golden Rose synagogue in Lvov. The iron doors date from the 19th century. Aparticular feature is the tower which during post-war repair works was raised even higher. The stone steps and the cellar remain. The tower served as aprison for the Lesko Jewish community which had judicial autonomy. The synagogue now houses the Art Gallery of the Bieszczady House of Culture. Parts of the bimah, stolen sometime before 1947, can now be seen in the house in Plac Konstytucji 3 Maja (once an Armenian shrine) where they were used as construction elements for the balcony, as well as in one of the houses in ul. Unii Brzeskiej. At the crossroads of ul. Berka Joselewicza and ul. Moniuszki. Erected in stone and rectangular in shape, it has an extension containing aprayer room for women. The inscription on the front wall proclaims: "What fear this place fills us with! There isnothing here but ahouse of God". The aron ha-kodesh is framed by half-columns crowned with atympanum, similar to that in the famous but no longer existing Golden Rose synagogue in Lvov. The iron doors date from the 19th century. Aparticular feature is the tower which during post-war repair works was raised even higher. The stone steps and the cellar remain. The tower served as aprison for the Lesko Jewish community which had judicial autonomy. The synagogue now houses the Art Gallery of the Bieszczady House of Culture. Parts of the bimah, stolen sometime before 1947, can now be seen in the house in Plac Konstytucji 3 Maja (once an Armenian shrine) where they were used as construction elements for the balcony, as well as in one of the houses in ul. Unii Brzeskiej. At the crossroads of ul. Berka Joselewicza and ul. Moniuszki.

The Jewish Cemetery

Legend has it that here is the resting-place of the founders of the Lesko Jewish community, some Spanish rabbis driven out of their country in the 16th century. The oldest of the remaining tombstone inscriptions reads as follows (ashortened version): "Here lies the pious man, Eliezer, son of rabbi Meshulam, may the memory of the righteous be blessed. He died on the 9th day of Tishri in the year 309 according to the abbreviated date record". The cemetery is three hectares in size and contains around five hundred matzevot. From the synagogue go down ul. Moniuszki (follow the route marked in blue). At the point where ul. Moniuszki and ul. Zrodlowa cross, alittle further back on the right there is agate with stars of David on it. Take the steps behind it and walk up.

Up to the German occupation the town had many houses of prayer. They were all in close proximity to the existing synagogue, whether on the other side of the street or where there was a block of dwellings (to the north west of the synagogue). There was the Old Synagogue (built sometime before 1838); the New Synagogue (located in the same building and used as a meeting-place by the communal fraternities); Sandzer Kloyz where the followers of the Halberstams from Nowy Sacz gathered (the rabbi of Lesko was a member of this community); and Sadygorer Kloyz, for the followers of Izrael Friedmann, opponents of the Nowy Sacz Chasidim.

|

"תמונת מחזור" תרצ"ו מה'חדר' בסאנוק

"תמונת מחזור" תרצ"ו מה'חדר' בסאנוק

Erected in stone and rectangular in shape, it has an extension containing aprayer room for women. The inscription on the front wall proclaims: "What fear this place fills us with! There isnothing here but ahouse of God". The aron ha-kodesh is framed by half-columns crowned with atympanum, similar to that in the famous but no longer existing Golden Rose synagogue in Lvov. The iron doors date from the 19th century. Aparticular feature is the tower which during post-war repair works was raised even higher. The stone steps and the cellar remain. The tower served as aprison for the Lesko Jewish community which had judicial autonomy. The synagogue now houses the Art Gallery of the Bieszczady House of Culture. Parts of the bimah, stolen sometime before 1947, can now be seen in the house in Plac Konstytucji 3 Maja (once an Armenian shrine) where they were used as construction elements for the balcony, as well as in one of the houses in ul. Unii Brzeskiej. At the crossroads of ul. Berka Joselewicza and ul. Moniuszki.

Erected in stone and rectangular in shape, it has an extension containing aprayer room for women. The inscription on the front wall proclaims: "What fear this place fills us with! There isnothing here but ahouse of God". The aron ha-kodesh is framed by half-columns crowned with atympanum, similar to that in the famous but no longer existing Golden Rose synagogue in Lvov. The iron doors date from the 19th century. Aparticular feature is the tower which during post-war repair works was raised even higher. The stone steps and the cellar remain. The tower served as aprison for the Lesko Jewish community which had judicial autonomy. The synagogue now houses the Art Gallery of the Bieszczady House of Culture. Parts of the bimah, stolen sometime before 1947, can now be seen in the house in Plac Konstytucji 3 Maja (once an Armenian shrine) where they were used as construction elements for the balcony, as well as in one of the houses in ul. Unii Brzeskiej. At the crossroads of ul. Berka Joselewicza and ul. Moniuszki.